European

Nuclear Society

e-news

Issue 7 Winter 2005

http://www.euronuclear.org/library/public/enews/ebulletinwinter2005/listening.htm

The concept of cognitive dissonance was introduced by Leon Festinger in a book titled A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance published in 1957, almost fifty years ago. The focus of this book was on a psychological condition that has certainly been experienced by all of us: receiving a piece of information that contradicts previously-held beliefs. Cognitive dissonance is the state arising from the realisation that one is now faced with an inconsistency in one’s system of beliefs. How serious is the feeling of unease resulting from cognitive dissonance and what individuals do to remove this feeling are the main subjects of interest of this book and of a lot of ensuing research. One example will at the same time make the concept clearer and show what it can be used for. Let us

|

|

consider a customer who purchases, say, an electric appliance. This very act is liable to arouse dissonance: the negative aspects of the action taken, as well as the positive aspects of alternatives (not purchasing, or purchasing something else) is dissonant with the decision. The purchaser will have to do something to reduce the ensuing psychological discomfort. In this context, one would conjecture that the effort exerted to reduce the tension should be proportional to the discomfort experienced1. Many experiments designed to investigate such situations |

in controlled conditions have confirmed this hypothesis2. The concept of cognitive dissonance does not just apply to the understanding of individual reactions in everyday situations. It can also be used to analyse cases where the dissonance comes from a discrepancy between an accepted theory and the occurrence of new facts that seem to give the lie to the said theory. It can be confidently predicted that, here also, cognitive dissonance reduction mechanisms will come into play.

These ideas can be usefully applied to the controversy surrounding

the peaceful use of nuclear energy. Both the supporters and the critics of nuclear

energy have encountered states of cognitive dissonance. Let us call them Pronukes

and Antinukes respectively for short and give two examples:

The Pronukes gave assurances that the operation of nuclear reactors would be perfectly safe but were nevertheless faced with a number of accidents, the most serious of them being Three Mile Island (for its potential impact) and Chernobyl (for its actual consequences). Their early response to the accident argument consisted of compiling risk compendia3 showing that other industrial activities entail much larger risks. As for Chernobyl, the standard answer, in the West at least, is that this accident is linked to a technology and a safety organisation that are not relevant anymore.

|

|

The Antinukes have always claimed that even low-level radiation is harmful but have not succeeded in providing unambiguous evidence for their claim. They answer that the needed evidence would be forthcoming if further research was undertaken.

Is one entitled to see in the responses of both parties mere attempts to reduce their respective states of cognitive dissonance? Third parties could be tempted to say yes and hence consider that the Pronukes' and Antinukes' positions are actually symmetrical. Such an attitude would apparently be justified as it would conveniently explain why the nuclear controversy has been inconclusive for so long.

One additional consideration can help to clarify the issue raised above. When an individual (or a group) is faced with a discrepancy between theory and observations, two options are available. One can either adjust/reject the theory to take account of the new observations or question the validity of the said observations because they do not fit the theory. In principle, both options have some value; they are complementary and in their judicious use resides the essence of scientific progress. In practice, how have the Pronukes and Antinukes dealt with their respective problems? By and large, the Pronukes have adjusted their theories and the Antinukes have questioned the observations. To come back to the examples provided above,

TMI and Chernobyl were not simply explained away. TMI was followed by the implementation of post-TMI measures on all operating PWRs; Chernobyl elicited the creation of the World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO) in order to leave no part of the world outside the reach of important safety information. These practical measures amount to recognising that the "theory" regarding the state of operational safety needed adjustments.

|

|

Claiming that further research will highlight detrimental effects of low-level radiation boils down to simply questioning the observations available. Why do so if not because they do not fit the Antinukes' theory on low-level radiation?

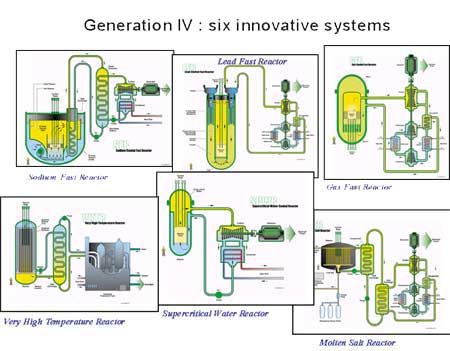

These two examples are typical of what the two parties usually do. On the one hand, the Pronukes adjust their theories most of the time through the implementation of practical measures; additional examples are Generation III reactors, the Generation IV project, the study of ageing mechanisms, etc. In one area at least, economics, the Pronukes' attack has been two-pronged: new reactor designs feature lower costs and the way costs are computed has evolved to take a fuller account of the externalities. On the other hand, the Antinukes systematically question the validity of figures or observations that do not support their basic tenets. They have done so regarding the economics of nuclear energy, uranium reserves, the amount of CO2 generated by nuclear power plants, the environmental impact of reprocessing. They have done so each time a quantitative assessment relating to nuclear energy was publicised. What should raise eyebrows is that they always manage to counter the assessments made by the Pronukes. No human being is right all the time. This is where the purported symmetry breaks down: the Pronukes demonstrate their human nature occasionally, while the Antinukes never go wrong.

Oh, by the way, there's one thing I almost forgot to mention. The philosophy of knowledge has given names to the two approaches for dealing with discrepancies between theory and observations: adjusting theory to facts is called the critical approach and questioning the facts that do not support the theory is called the dogmatic approach.

1 This, by the way, is the reason

why seasoned sales attendants will always endorse your choice whenever they

notice that the decision was difficult.

2 See for instance the first chapter of Cognitive Dissonance:

Progress on a Pivotal Theory in Social Psychology, edited by Eddie Harmon-Jones

and Judson Mills, APA Books.

3 For risk compendia, see

ENS NEWS issue no 2, autumn 2003.

![]()

© European Nuclear Society, 2005