|

|

Issue No. 19 Winter

|

|

ENS News |

|

ENS Events |

|

Member Societies & Corporate Members |

|

Two Phase Flow Westinghouse is Awarded Watts Bar Units 2 Completion Contract Bulgarian Nuclear Society Annual Conference ‘Nuclear Power for the People’ |

YGN Report |

|

European Institutions |

|

ENS World News |

ENS Members |

| Links to ENS Member

Societies Links to ENS Corporate Members Editorial staff ______________________ |

| _____________________ |

| Pime

2008 10 - 14 February 2008 in Prague |

| _____________________ |

____________________ |

|

____________________ |

|

____________________ |

|

|

|

|

|

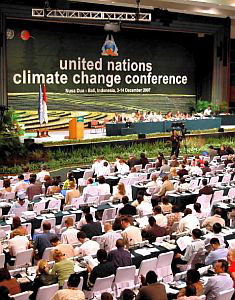

the developing countries will join around the table, together with the states that are committed to the Kyoto Protocol. The discussions will focus on a long-term goal for global greenhouse gas emissions reductions and on enhanced action on “mitigation”, “adaptation”, “technology development and transfer” and “finance and investment”. Finally, the Bali outcome also delivered an agreed text on deforestation, technology transfer, adaptation and carbon markets.

In addition to the deal’s 'character of inclusiveness', another aspect might be perceived as positive. Never in the history of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiations, has a working agenda been so short-term and detailed. The first post-Bali meeting of comparable importance in terms of content and international character is supposed to take place '…as soon as is feasible and not later than April 2008'1. Truly, going beyond simple optimism, this way of tackling the issues could well be seen as a make-or-break deal. But in whose interest is it? By the time of the next COP meeting, in Poznan, Poland in 2008, the world will know whether the Bali Action Plan is a success or a failure.

While there are reasons for optimism about the way the global talks proceeded, this text reveals a certain concern about the debate on nuclear within the frame of the climate change negotiations. Those who are familiar with UN climate change meetings shrug their shoulders, while others might be shocked to hear that up until now nuclear has, in fact, never been a subject of debate or considered part of the official negotiations within the framework of the global climate change meetings. The well-documented exclusion of nuclear from the basket of technologies eligible for the Clean Development Mechanism has mainly been debated on the fringes of the meetings - in corridors and restaurants around the conference centre. What’s more, the political delegations have never made a serious effort to bring the issue to the debating table in a constructive and open way. To put it straight: after many years of hushing up the issue in the official negotiations and an erosion of the quality of the debate on 'content' , one can say that, since Bali, the debate on nuclear in the context of international negotiations on climate change appears dead. The obvious question follows, is it really an issue of concern for both the political delegates and the nuclear community?

On December 13, around lunchtime, two official nuclear side events were simultaneously organised within the conference premises. While the World Nuclear Association organised an event that focussed on Indonesia's approach to nuclear energy, in another room at the conference centre, the Heinrich Boll Foundation (HBF) staged an event entitled Nuclear energy: myth and reality. The WNA event featured, among its speakers, the Indonesian Minister for Women Empowerment. The HBF event presented expert views from Europe, |

|

Australia, Brazil, South Africa and India on 'the role of nuclear energy in combating climate change', and aimed to present alternatives based on their observation that '… as nations worldwide seek to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, nuclear energy is promoted as a solution to climate change'2.

As the two events were taking place simultaneously and only a few rooms away from each other, I walked from one event to the other and back again, just to grasp what was going at in each event3. I must stress at this point that I do not want to question or criticise the intentions and professionalism of the organisers and speakers at both events. Instead, I would rather present what happened at the events as a metaphor for the overall state of the nuclear debate at climate change conferences4.

What was interesting about the two events was that while the pro-nuclear event presented the case of several countries that have launched or considered launching nuclear, and promote nuclear technology as a valuable solution to climate change, the anti-nuclear event focused on the opposite by highlighting those countries that are phasing out nuclear or claim that it is a non-option. The WNA event focussed on Indonesia and on other countries in the East. The HBF event, however, stated that the situation in Europe is best proof of the fact that nuclear is no solution because no plants have been ordered in Europe for decades and countries like Belgium, Sweden and Germany are currently phasing out nuclear. Finland was presented as 'the exception that proves the rule'. In addition, the HBF event reported on cases of 'bad government policy' in Brazil, South Africa and India that are guilty of '…failing to involve civil society in a proper way…' in the debate about nuclear. They cite these examples to support their claim that nuclear offers no solution to climate change.

Having taken the time to reflect on what happened there, I would like to make some observations that, I believe, deserve further analysis and discussion. This text does not allow time for broader and deeper analysis in order to provide further evidence to back up my observations, but there will obviously be more opportunities to do this later.

Summarising (and, admittedly, simplifying) 10 years of nuclear debate within the framework of the UNFCCC one can observe that the initial irritation and repugnance of the anti-nuclear lobby in the first years after the Kyoto conference was followed for many years by indifference and ignorance. The symbolic exclusion of nuclear from the CDM was regarded by most anti-nuclear NGO's as the final nail in the nuclear coffin. In recent years however, the nuclear community has found a new voice to articulate its message, encouraged by the 'nuclear renaissance' in the East and the West. During this period the starting point for the discussion was evidence of the emissions avoidance or reduction potential of nuclear energy. The focus of the debate switched roughly from technicalities and arguments about the risks of nuclear energy to discussions about policy and the economics of nuclear within the context of a 'climate-friendly' energy mix. In parallel, outside the UN negotiation rooms, some countries started to openly “show their hand” by explicitly favouring or rejecting nuclear in their national energy policies. As this anecdote shows these themes have been seized upon by NGO's at UN meetings.

My initial observation is that in international negotiations such as the UNFCCC conferences or the UN Commission on Sustainable Development meetings, countries keep on skirting around the nuclear issue instead of showing willingness to bring it in out into the open and discuss it in a transparent way. At the UN Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD1 that took place in New York in May 2007, the primary focus was on energy. Participating countries once again failed to take a joint position on nuclear, not because of ‘the complexity of the issue’, but because it simply wasn’t discussed. Many countries (to some degree supported by the EU position) do share the common view, however, that the responsibility for deciding whether or not to include nuclear in national energy policies should be made at the national level. A few months after CSD15 however, the Global Nuclear Energy Partnership (GNEP) announced that already 16 nations had agreed to sign up for GNEP. Another 22 countries were candidate partners and observers, making a total of 38 countries that are somehow involved with GNEP (see Nucnet 2007-10-02). Other countries that have joined GNEP since then are Canada, the Republic of Korea and Italy, the latter being one of the countries that has traditionally spoken out against nuclear at previous climate change meetings.

Recent developments have clearly shown that countries refrain from taking a position on nuclear in the context of international political commitments but do increasingly show, however, an eagerness to strengthen their position in the global economy by 'tuning' into international nuclear research and development programmes. Interestingly, the initiatives on involving civil society in the siting process for radioactive waste disposal sites provide further evidence for this line of thinking. Although it is of course the fundamental right for local citizens to become (voluntarily) involved in a proposed siting process, one can observe that participation remains confined to the local level, instead of enlarged to the national level, and that the participatory siting process remains deliberately decoupled from the (nuclear) energy debate.

The second observation is that the debate on nuclear 'in the observer arena' of international political meetings such as those of the UNFCCC and CSD is hollow and virtually dead (as suggested in the introduction). It will remain so as long as both 'sides' make no effort to overcome their polarised positions. I am not suggesting here that both sides should sit around the table and talk things through. We all know that this has been tried many times before, without success. The water that separates the two is generally perceived to be too deep. Today, the alternative approach of both sides appears to be to advocate their case by making reference to (good or bad) political practices, hereby paradoxically building on positions of countries that fail to stand up for those positions themselves in official negotiations. For the observer debate, or the scientific and social debate in general, the result is that both sides continue 'to talk next to each other', in Bali this literally meant in adjacent rooms.

By now, the reader might wonder where this story is leading to, especially in view of what I suggested in my introduction, one might think that there is no problem at all. Knowing that nuclear can be competitive in certain conditions companies will only invest in it if there is a legally binding framework and if it backed up by stable national political support in their particular country. In the face of climate change, many countries show (again) support, which makes mid- to long term investment (again) interesting. Whether this 'nuclear renaissance' is a reality or rather a self-fulfilling prophecy of the industry is a subject of reflection that goes beyond the scope of this text.

My central thesis here is to point out that there is a fundamental flaw in the reasoning of many nuclear communities (advocacy groups, industry and research), their anti-nuclear opponents and many politicians, including some who are in favour of nuclear. The flaw has to do with the way civil society should be 'engaged' in the social justification of complex risk-inherent technologies such as nuclear. Today, all policymakers, whether at industry, research or national and international political level, see 'societal support' as a prime condition for the justification of the use of complex risk-inherent technologies in general and of nuclear technology in particular. Never before, has civil society been more 'present' in the debate around nuclear than today. But this is the crux of the problem - its appearance is basically “virtual”: civil society is present as a 'subject', not as a partner. It is studied, questioned, psychologically mapped and categorised, all with the objective of adapting, fine-tuning and simplifying the information it needs to 'finally understand' and accept or reject the nuclear option. In all these efforts 'to get the message through', one forgets that the ultimate societal support may be found by engaging civil society itself 'bottom-up' in the actual policy process as such: 'joint problem solving' that should even be preceded by 'joint problem definition'. Instead of this, communication with civil society and the public at large is still seen as a 'next step' after round-up of the technology assessment exercise 'internally'. The result is that the nuclear and anti-nuclear communities and those politicians who are in favour of nuclear tend to do their work within their friendly little circles first, and then 'step outside' in order to seek acceptance for their 'product'.

Civil society is pre-determined and written into strategies according to the desired goal. The nuclear community wants to seek trust and confidence within civil society, but only by way of providing 'factual evidence' and transparent information on its activities, and not by inviting it to take part in a joint justification exercise. The anti-nuclear NGO's, for their part, see no need to double-check for trust and confidence with civil society for their activities and messages, as they quite simply claim to represent it.

While, for several reasons, we see national politics avoiding to engage civil society in political deliberation on a national or international level, both the nuclear and anti-nuclear community now have the opportunity 'to give a good example'. To make my position clear, I am not arguing in favour of a broad societal debate on nuclear because I see this as a way to support nuclear (not as a way to phase it out), but because nuclear exists as a politico-economical dynamic that develops outside most citizens’ considerations and remains separate from any need for joint societal justification.

The situation seems to be one of stalemate. While the anti-nuclear movements should do a critical self-assessment in order to find out if and how they actually 'represent' civil society in their anti-nuclear messages, the nuclear communities should invite civil society to take part in a justification exercise of which the outcome might well turn against them. Moreover, whereas it seems evident that it is not the pro- or anti-nuclear community that should initiate and organise societal debate, but that it is the responsibility of national and international politicians, we do see political dynamics hijacked by politicians’ fear that they might be transcending their own short-term legislative commitments and by the very limits that a system of traditional representative democracy imposes on organising such societal involvement. Last but not least, to make matters worse, one might wonder what civil society actually is, and how it can be approached, organised and engaged in debate in a practical way.

Not surprisingly, there are no clear-cut answers or readily-available bullet-point recommendations for such a complex issue. One thing is certain, though, although we have to take these complexities and limitations seriously, they cannot be used as an excuse to escape responsibility, whomsoever on thinks is responsible for what. In addition, even if there were shared evidence of the need for a broad societal governance process, the question “why this process should especially be organised around nuclear, and not for other complex risk inherent technologies such as genetically modified crops or nanotechnology?” would have to be asked. The answer is, of course, that these technologies would also need to be subjected to a fully inclusive governance process.

The objective of this text was to raise awareness in a certain way of perceiving the situation, and to invite feedback and discussion. I dare to conclude by making another 'simple' statement. We all know it would be naïve to think we could try and replace the actual politico-economical rationality that “rules the world” with a new model of a more emancipated citizenry. There is simply no need to do so. Business and industry ask 'enabling frameworks' that should be guaranteed by politicians. It is in the defining and fine-tuning of these frameworks that civil society could be better engaged in, and this requires political will as well as motivation from research and from industry. Consider this: it makes no sense to organise inclusive reflection on the subject of nuclear energy outside a broad-ranging and comprehensive energy debate; a debate that also needs to link with other thematic issues that need to be tackled 'for the better of society' such as water, climate change, health and agriculture. Advocates and opponents of nuclear should accept that the outcome of any inclusive political governance process could also prove to be a rejection or acceptance of nuclear. At least the decision will have been supported as robustly as possible.

Finally, it is worthwhile to do an assessment of nuclear technology 'from within'' in order to study aspects of risk perception and governance, balances of benefits and burdens, responsibilities towards future generations and interconnections with the possible or actual misuses of the technology, such as proliferation and terrorism. The research should anyway be trans-disciplinary as well as inclusive. For those who might not know, this kind of research is already being carried out within the nuclear community, and it remains quite unique. Trans-disciplinary and inclusive analysis of nuclear can be carried out anywhere - in universities, in industry communication campaigns, in learned societies’ working groups and within UN observer platforms. It costs virtually nothing, as all you only need is a brain, a certain engaged detachment (or detached engagement) and a sense of curiosity.

1Decision -/CP.13: Bali Action Plan. See this and other documents on unfccc.int/2860.php

2United Nations Climate Change Conference COP 13 and CMP 3 Bali, 3-14 December 2007; Daily Programme of 13 December 2007. See unfccc.int/meetings/cop_13/daily_programme/items/4162.php

3Speaking from experience with UN meetings, one could assume that the UNFCCC secretariat, in coordinating the agenda of side events, did not schedule the two events simultaneously 'by accident'.

4Traditionally, also the IAEA organises a nuclear event at every

climate change meeting. While their intention is to take

a neutral and factual stance 'by design',

one can observe that obviously their interventions are perceived as 'pro-nuclear'

by observers and delegates. As the example I give is meant as a metaphor

for more general observations, a reflection on the effect

of the contributions of

the IAEA is beyond the scope of this text.

| |